By Stephen Hill

A whole generation of schoolchildren are missing out on entrepreneurship education across the globe. This is a stark conclusion from the collective assessments of over 2,000 national experts across the 50 different economies featured in the GEM 2021/2022 Global Report. In addition to the Adult Population Survey (150,000 respondents) described in the Global Report, GEM National Teams also conduct a National Expert Survey (NES), involving at least 36 identified and approved national experts in each economy, and often more. Each expert is asked to score 13 specific elements of that economy’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, labelled by GEM as Entrepreneurial Framework Conditions (EFCs), one of which is Entrepreneurial Education at School.

The specific questions ask experts to score, on an eleven-point scale from completely false (scored as zero) to completely true (scored as ten), a number of different statements about each of the EFCs. For Entrepreneurial Education at School (abbreviated here as EES), the specific statements are:

“In my country….

- teaching in primary and secondary education encourages creativity, self-sufficiency and personal initiative,

- teaching in primary and secondary education provide adequate instruction in market economic principles, and

- teaching in primary and secondary education provides adequate attention to entrepreneurship and new firm creation.”

Scores for these three elements are then combined into an overall score for that framework condition. On the face of it, these three elements do not appear to be overly-demanding. Objective observers might reasonably expect most economies to be pretty good at these, especially compared to other EFCs such as access to finance, market openness, physical infrastructure etc (a full list is on page 86 of the Global Report). Yet the collective assessments of those national experts indicate the opposite – most countries are failing to provide sufficient entrepreneurial education at school. Of the 13 EFCs, Entrepreneurial Education at School was rated last of all in 39 of the 50 economies participating in GEM 2021 – so EES scored lowest in more than three-quarters of those economies.

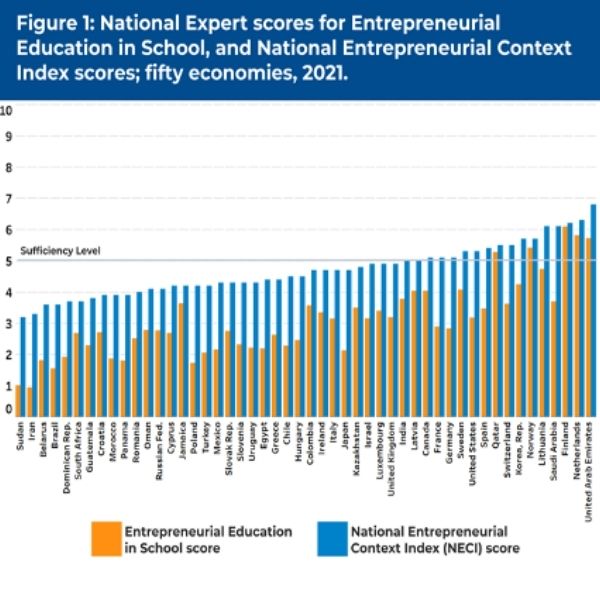

Since 2018, GEM has summarised experts scores across the framework conditions into just one number – the National Entrepreneurial Context Index, which is the average of all 13 EFC scores for that economy. Figure 1 plots each economy’s score for Entrepreneurial Education at School alongside that economy’s National Entrepreneurial Context Index score. The results are at best startling. If a score of 5.0 (half way between zero and ten) is regarded as sufficient, only five of the 50 economies scored as sufficient for Entrepreneurial Education in School: Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. These economies are all classified by GEM as Level A in terms of average incomes, meaning each had a GDP per capita greater than $40,000 (Level C economies had GDP/per capita less than $20,000, while Level B are in between). However, prosperity is no guarantee of EES sufficiency, as 14 other level A economies scored as insufficient.

Source: GEM NES 2021

Source: GEM NES 2021

A number of prosperous economies scored particularly badly. Examples in Europe include France (2.89), Germany (2.83), the Russian Federation (2.77) and Poland (1.73). Examples elsewhere include Turkey (2.06), Uruguay (2.22) and Japan (2.13). On few other indicators would Jamaica score better than Switzerland, or Kazakhstan better than Luxembourg! It is clear that many relatively well-off countries attach little priority to Entrepreneurial Education at School. This is not necessarily to say that entrepreneurial education is neglected overall – in many economies, another EFC, Entrepreneurial Education post-school (i.e. colleges and universities), scored much better. There was only one economy (Finland) where EES scored higher than Entrepreneurial Education post-school. We saw earlier that in only five economies was EES scored as sufficient or better (score of 5 or more). For Entrepreneurial Education post-school, 16 economies scored as sufficient or better.

Of course many poorer countries score badly on EES. Yet Figure 1 shows Level C (low-income) Colombia and India scoring better at Entrepreneurial Education in School than 15 Level B (medium-income) economies, and nine Level C economies. So shortages of income can be overcome, but presumably only where there is sufficient will to do so.

This brief article has demonstrated that entrepreneurial education at school is typically rated poorly by national experts, both in terms of absolute scores (with eighteen economies with EES scored at half or less sufficient, i.e. scores of <=2.5), and relative to other framework conditions (EES score at half or less of that economy’s NECI score in 11 economies). The long-term consequences of poorly performing entrepreneurial education in schools are as yet unknown, but could include:

- little awareness of entrepreneurship as an option among young people,

- young people with little understanding of how their economies work, and hence illequipped to hold their politicians to account,

- an inability to appreciate the personal and financial investment required to transition a new into an established business, and hence an endless cycle of shortlived new businesses.

There is an urgent need for research that assesses the relationship between Entrepreneurial Education in School scores and other dimensions of contemporary or subsequent entrepreneurial performance, such as the level of entrepreneurial activity (TEA or Total early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity), or the ratio of TEA to Established Business Ownership.

In the meantime, and in advance of such research, a challenge to governments, policy-makers and to educators:

Make the 2020’s the decade in which Entrepreneurial Education in Schools went from being the lowest-rated Entrepreneurial Framework Condition to become the highest-rated.

Such a transformation could catapult both the level of entrepreneurial activity among young people and the rate of transition from new to established businesses. Both achievements would mean more jobs, more incomes and more individuals realising their own potential.

Dr Stephen Hill is the Lead Author of the GEM 2021/2022 Global Report.