By Peter Josty

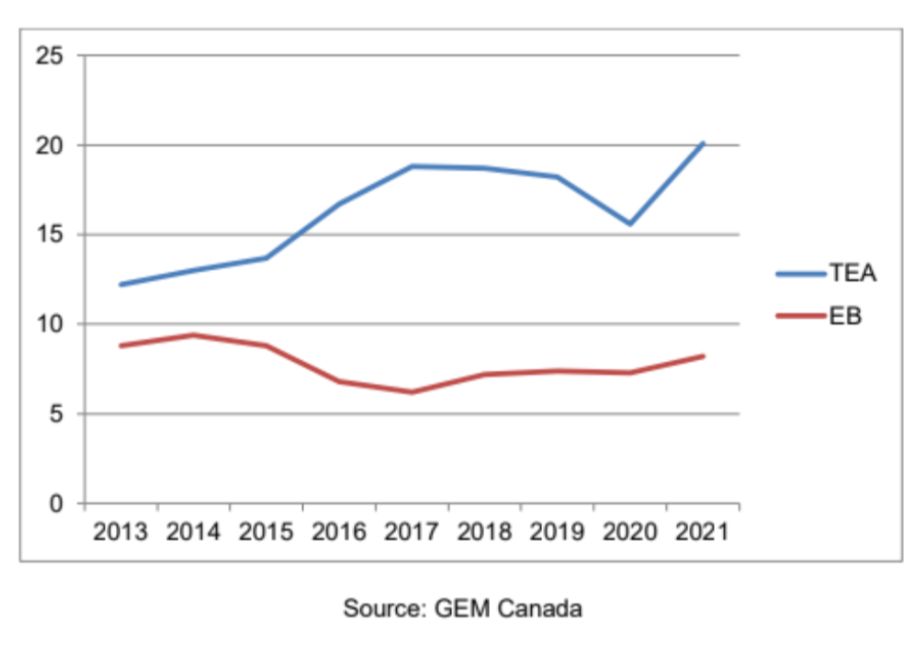

The percentage of the population involved in entrepreneurship in Canada has increased more than 50% over the last ten years, according to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. In 2021 about 20% of the adult population was involved in planning or starting up a business.

The graph below shows the evolution in Canada since 2013 using the GEM database.

TEA (Total early stage entrepreneurship activity) is a combination of two numbers – nascent entrepreneurs, those actively starting up a business and owner managers of a business less than 3.5 years old.

EB (established businesses) are owner managers of a company more than 3.5 year old.

In both cases the numbers refer to the percentage of the adult population (age 18+) engaged.

The TEA rate has crept steadily upwards since 2013, with a dip in 2020 due to COVID, while the EB rate has remained fairly constant.

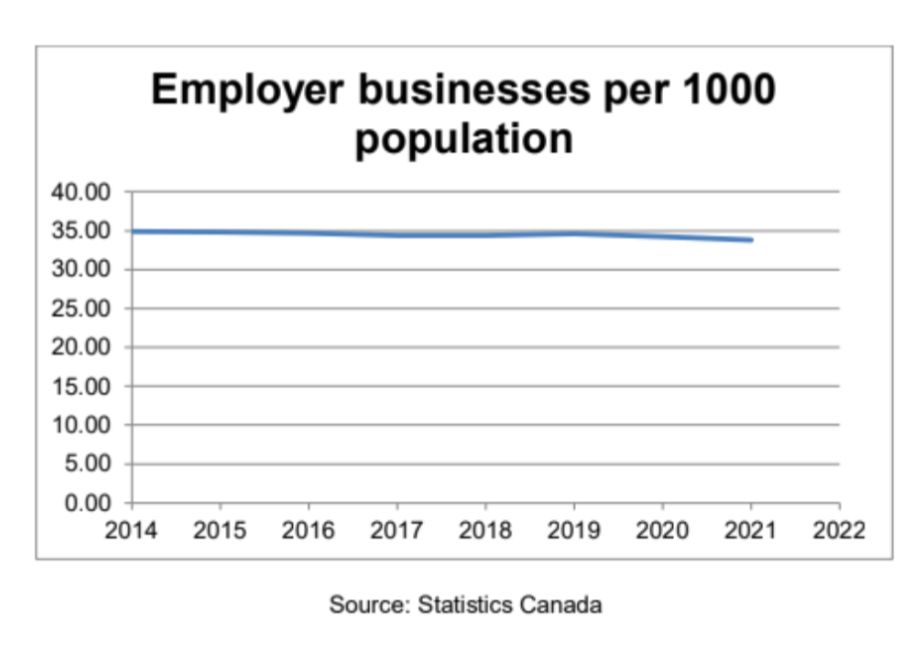

Statistics Canada data confirms that the number of firms, adjusted for population growth, has remained roughly constant since 2014.

Is this just a Canadian phenomenon? If you look at the GEM data for several other countries you see exactly the same phenomenon. TEA has risen significantly from 2013 to 2021 in the UK (by 80%), France (by 70%), Germany (by 40%) and the US (by 30%). This compares with the rise in Canada of 70%. So this is certainly not a uniquely Canadian situation.

The EB rate in the other countries has also remained fairly constant over the same period.

So what is going on? The real answer is that at this point we don’t know for sure. As highlighted in this research paper, there could appear to be several possibilities:

- More people are involved in each new startup. Might this be because startups are becoming more complex requiring more diversity of skills?

- There may be more hybrid entrepreneurs – people who work for a large company and work to develop opportunities either for their employer or for themselves.

- More business consolidations are happening early in the life cycle.

The negatives.

The larger question is: does this really matter? The hard facts are that from an economy wide perspective, large businesses are much more productive than small business. In Canada 2.4 million people (15.1% of the labour force) work for large companies, and produce 48.1% of the GDP, while 13.7 million people (84.9% of the labour force) work for small and medium sized companies and produce 51.9% of GDP. So, a person working in a large company, on average, produces 5 times as much GDP as a person working in a small or medium sized company.

If entrepreneurship is such a good thing, then why is Canada a laggard in innovation and R&D spending?

Does it matter? The positives

However, it has been well established that entrepreneurs and other outsiders are a main vehicle for introducing radical new technologies to the marketplace. Just think why Tesla is the leader in electric cars rather than GM or Toyota. The current rise in tech startups in Canada is likely a manifestation of this.

Several large sectors of the Canadian economy, such as retail, construction and healthcare, rely on small and medium sized firms, and they make a significant contribution to the overall economy and provide valuable employment.

Also, in a period of economic turbulence, such as we seem to be entering now, having entrepreneurial skills is a valuable attribute, whether in a large company or a startup. The key role of the entrepreneur is to identify opportunities, and then generate the enthusiasm, vision and plans needed to create a successful venture.

Conclusion

Although most startups don’t generate much wealth, innovation or jobs, nevertheless some of them do, and this is a key driver of economic growth.

Peter Josty is the Executive Director of THECIS (The Centre for Innovation Studies) and head of the GEM Canada Team. A version of this article first appear on the THECIS website.