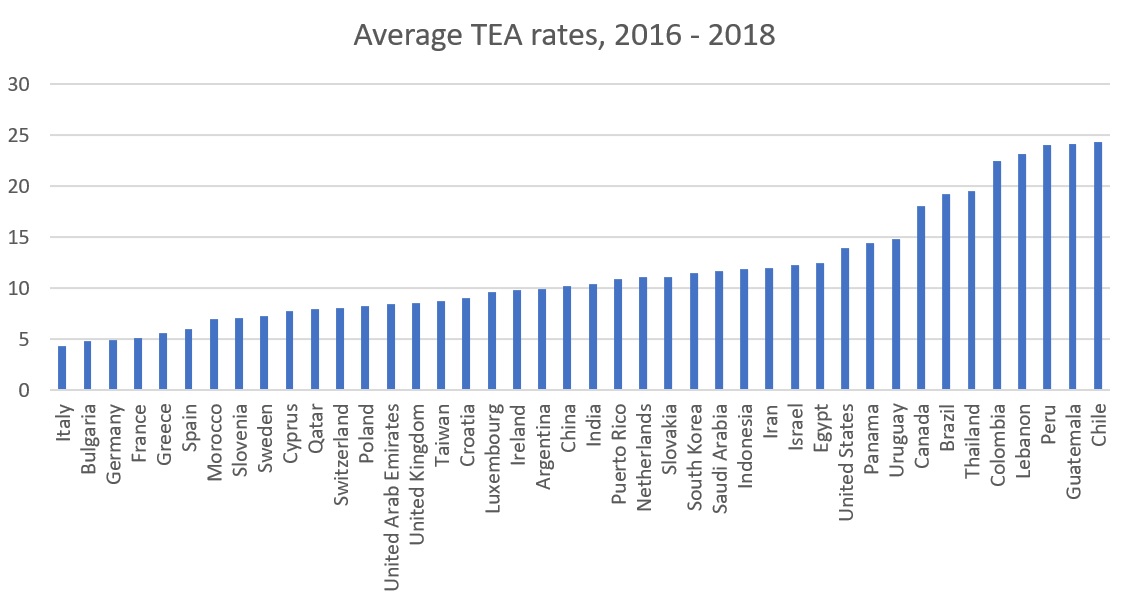

Every year, GEM National Teams survey a representative sample of their economy’s population to determine what proportion of their population is involved in early-stage entrepreneurship. Early-stage is defined as the percentage of an economy’s 18-64 population who are either a nascent entrepreneur (actively planning a new business) or owner-manager of a new business (within the first 42 months of starting). The result is an economy’s Total early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) rate; an indicator used by many economies to broadly gauge what percentage of their adult population is trying to start a new business.

Below is a chart of the 42 economies that participated in all three GEM survey cycles from 2016 to 2018, graphed by their average TEA rate over those three years:

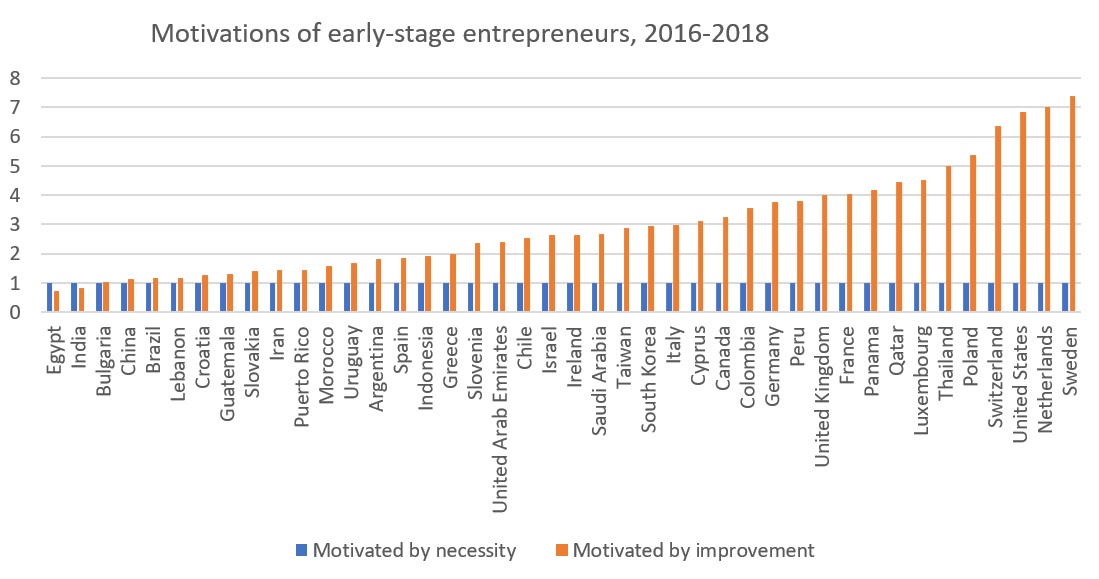

While these rates are quite useful as a benchmark for entrepreneurial activity, particularly as it might change over time, GEM produces other indicators that can enhance understanding of the quality and nature of this early-stage entrepreneurship. GEM’s Motivational Index calculates the ratio of necessity-driven entrepreneurship to improvement-driven entrepreneurship among early-stage entrepreneurs. This index reveals what proportion of an economy’s early-stage entrepreneurs have started their own business out of necessity (because they had no better choice for work); versus those that started a company because they saw a business opportunity.

Below are the Motivational Index rates for the same 42 countries with “necessity-driven entrepreneurs” set to 1. This means economies with a rate lower than 1 have more necessity-driven entrepreneurs in their economy, while countries at the higher end of the spectrum such as Sweden have more than 7x the number of improvement-driven entrepreneurs than necessity-driven.

Many economies view these rates to determine the quality of early-stage entrepreneurship. Higher rates of improvement-driven entrepreneurship can reveal two broad insights:

- That the entrepreneurial space in their economy is dynamic and encouraging, and;

- That their formal employment sector is sufficiently strong to provide work for those who would rather not become entrepreneurs.

This element is often neglected in mainstream coverage of entrepreneurs. In order to truly understand an economy’s entrepreneurial sector you have to if individuals are pursuing that activity out of necessity or opportunity.

Analysis by Forrest Wright (GEM Global Data Team)